NASA

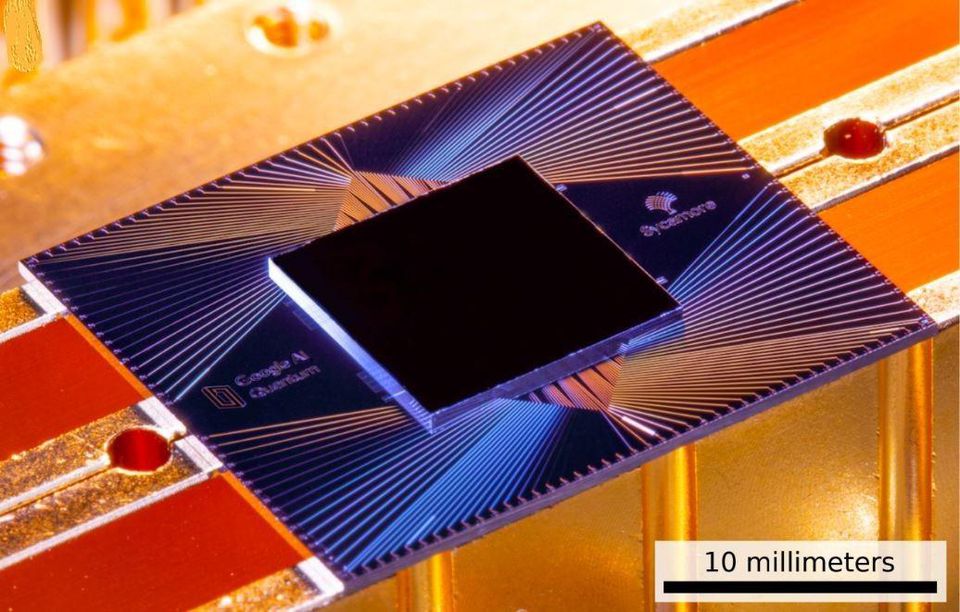

Quantum supremacy was supposed to be a significant benchmark to signal that quantum computers could finally solve problems beyond the capability of classical computers. The term "quantum supremacy" was first used in a 2012 paper by one of the world’s leading theoretical physicists, John Preskill, Professor of Theoretical Physics at Caltech. Last month, a leaked research paper declared that Google GOOGL +0% had attained quantum supremacy. According to the paper, Google’s 53-qubit quantum computer, called Sycamore, had solved a problem in a few minutes that would take a classical computer 10,000 years to solve.

IBM was the first and loudest to cry foul

Dario Gil, head of IBM IBM +0% quantum research, described the claim of quantum supremacy as indefensible and misleading. In a written statement, he said, “Quantum computers are not 'supreme' against classical computers because of a laboratory experiment designed to essentially implement one very specific quantum sampling procedure with no practical applications.”

Yesterday, IBM published a paper that backed up that claim. The paper points out that Google made an error in estimating that a classical computer would require 10,000 years to solve the problem. In a discussion last week, Bob Sutor, Vice President, IBM Q Strategy & Ecosystem, also told me that IBM believed the 10,000-year estimate was an overstatement.

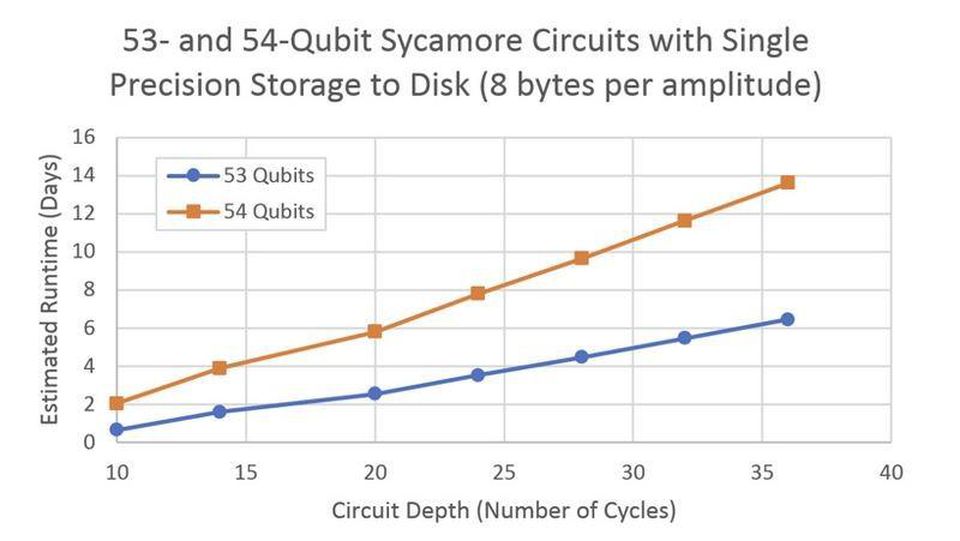

According to IBM’s blog, “an ideal simulation of the same task can be performed on a classical system in 2.5 days and with far greater fidelity." The blog post went on to say that 2.5 days is a worst-case estimate. Additional research could reduce the time even further.

Google overstated its 10,000-year estimate based on an erroneous assumption that the RAM requirements for running a quantum simulation of the problem in a classical computer would be prohibitively high. Google used the time to offset the lack of space, resulting in its estimate of 10,000 years.

IBM used both RAM and hard drive space to run the quantum simulation on a classical computer. Additionally, it incorporated other conventional optimization techniques to improve performance.

IBM

There are other factors, as well. The number of computations that can be achieved on quantum computers is limited by how long qubits can maintain their quantum states--usually about a nanosecond. On a classical machine, there is no limit on how many times an algorithm can be run.

Next stop, Quantum Advantage

It’s time for us to look past quantum supremacy and begin focusing research efforts toward a broader, more realistic capability called quantum advantage. Quantum advantage will exist when programmable quantum gate-computers reach a degree of technical maturity that allows them to solve some, but not all, real-world problems that classical computers can’t solve (or problems that classical machines require exponential time to solve).

It’s accepted that quantum machines will eventually be able to solve problems that classical machines can't solve. However, it's unlikely that quantum computers will replace classical computers. The long-term future of computing will be a hybrid between quantum and traditional machines.